Climate

During the six months of Seattle’s 2023 cruise season, almost 600,000 people will fly here to take cruises. The airplane flights plus the cruise ships will emit over 2 million tons of greenhouse gasses; about a third as much as is emitted by the entire city of Seattle in a whole year.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) gives us less than 10 years to radically reduce global emissions or face irreversible devastation. We cannot reduce emissions if we continue to expand fossil fuel intensive activities.

How cruise ship GHG emissions are measured: Knowing the amount and type of fuel that was burned by each cruise ship during its journey to Alaska and back would provide a fairly direct path to measuring Seattle’s cruise ship GHG emissions. However, this information is not readily available, either to the public, or, apparently, to local governmental agencies. Hence, emissions must be estimated using more indirect methods. Below, we demonstrate one way to estimate emissions using online carbon calculators and publicly available data, and explain why the resulting number differs from the figure published by the Port of Seattle.

From the associated flights: 763,000 tons

Total: 1,883,000 tons (about 1.9 million tons)

Emissions from Seattle’s 6-month cruise season vs. a whole year of emissions from the entire city: The updated 2018 figures from Seattle’s 2020 Greenhouse Gas Emissions Inventory (p.13) show the expanded emissions for the whole city were 6,318,500 tons. Hence, the ships and planes operating during the six-month cruise season produce emissions equal to about a third (30%) of the emissions from the entire city of Seattle for the entire year.(1)

Shore power averts only a tiny fraction of GHG: At one of Seattle’s two cruise terminals, ships can use shore power while at berth, which means they can plug into the city’s electrical grid instead of burning fuel. In 2022, shore power use averted 2178 tons of GHG emissions. Unfortunately, this represents only about 1/10 of 1% of that year’s cruise sector emissions. If shore power had been available at both terminals in 2022 and if all ships used it – the Port of Seattle has suggested this may happen by 2030 – the amount of averted GHGs would have increased to about 12,000 tons, but this is still only one-half of 1% of that year’s cruise sector emissions. Clearly, shore power does not offer an adequate solution to cruise’s destructive effects on the climate.

How does this compare to what the Port says about GHG emissions from cruises? The Port’s 2019 Emissions Inventory (p.4) reports that “ocean-going vessels” emitted 58,539 tons of CO2e. There are two problems with this number:

- The number is based on the Puget Sound Emissions Inventory (PSEI) from 2016, which counts ship emissions only between Seattle and the Canadian border(2); this distance represents about 5% of the length of the total journey of the Alaskan cruises, which travel between Seattle and Skagway, Alaska.

- The category “ocean-going vessels” includes container ships, bulk cargo ships, and tankers, as well as cruise ships; emissions for cruise ships are not reported separately.

Thus, the Port’s number both obscures and dramatically undercounts the effects of Seattle’s cruise industry on the climate.

It is important to note that the numbers in the PSEI itself (on which the Port’s emission numbers are based) are not based on direct measurement of total fuel burned by the ships. Rather, they are estimates of cruise ship emissions, based on factors including routes, engine power, speed, fuel type, etc.(3)

The PSEI does list an emissions total just for cruise ships, in the limited geographical area described above: 59,417 tons. Note that the PSEI is using the unit “American short tons;” this number is equal to 53,902 metric tons.(4)

What do Seattle and King County say about cruise ship emissions? Emissions inventories from Seattle (2018, p. 13) and King County (2017, p.10) include entries for marine vessel emissions; these numbers are also based on the PSEI. They, like the Port, combine cruise ship emissions with emissions from other ocean-going vessels, and also do not count any emissions beyond the Canadian border.

Methodology and supporting data

A word on passenger numbers. Based on a phone conversation with Port Commission Policy Manager Aaron Pritchard on January 21, 2020: the cruise industry standard is to count both embarking and disembarking passengers; this results in approximately double the actual number of people who take cruises. The Port of Seattle reported 1.2 million passengers in 2019; this means there were actually closer to 600,000 distinct people who took cruises.

How many flew: At the March 12, 2019 Port meeting, Mike McLaughlin, Director of Cruise Operations, said 80 to 90% of cruise passengers flew to Seattle to start their cruises.

Information about ships and voyages, including trip length and number of passengers, is from 2019 Port of Seattle Cruise Ship Arrivals.

Emissions calculations for both cruises and flights were computed using carbon calculators on websites that also offer to sell carbon offsets to travelers.

Cruise ship emissions were calculated using the website myclimate.org. It provides estimates of 100-year global warming potential. This site estimates the total emissions for each ship, based on factors including number of passengers, length of voyage, speed, and fuel type(5), and then apportions the total ship emissions to individual passengers, based on the type of cabin they are staying in (standard, suite, or penthouse) and number of occupants; occupants of larger cabins are assigned a larger proportion of the total emissions than occupants of standard cabins. We reverse the process: emissions were calculated for each cruise passenger individually, and added up to get the total emissions from all of the ships. Table 1 organizes information about ship calls and number of passengers by the ship size categories and voyage length used by the calculator; Table 2 shows the computations of GHG emissions for all passengers in each ship size category for each length voyage.

Lacking specific information about how many passengers were accommodated in each type of cabin, conservative (and simplifying) assumptions were made that all passengers were in standard cabins, with double occupancy. Since standard cabins are assigned a smaller proportion of total emissions than larger suites or penthouses, this results in an underestimation of the total emissions.(6)

Flight emissions were calculated using the site atmosfair.de. This site was chosen partly because it incorporates the effects of high-altitude non-CO2 emissions (such as water vapor) into its computations, resulting in a more accurate estimation of global warming potential. An additional conservative assumption was made, that all passengers flew coach class; this also likely underestimates the total emissions.

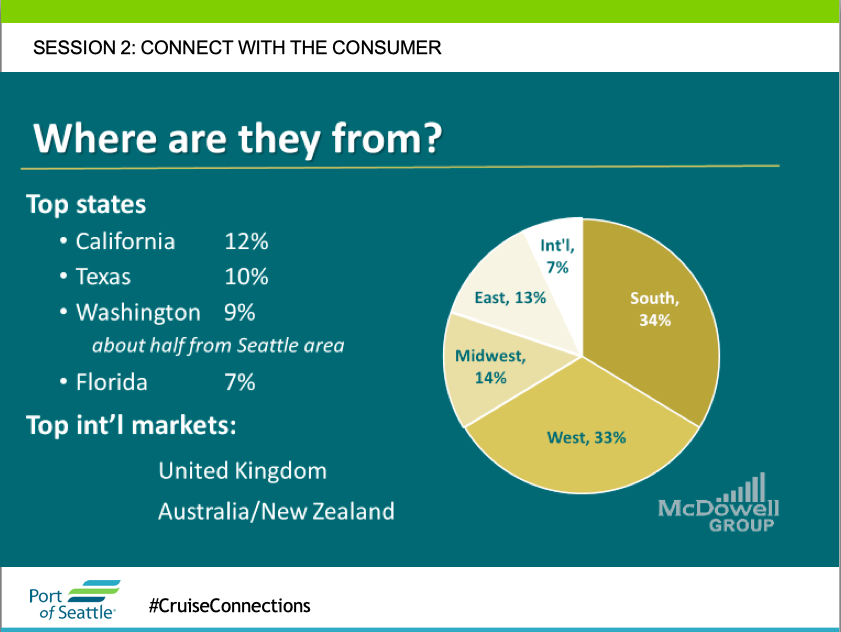

Information on where people’s flights originated is from a power-point presentation shown at the 2019 Cruise Connections conference, held in Seattle. For each region or state from the slide below, a centrally located city was chosen as a proxy for the whole region/state.

Table 3 shows the computations for flight GHG emissions.

Footnotes:

(1) Seattle’s Inventory includes flight emissions only of Seattle residents, and includes only a tiny fraction of cruise ship emissions: those emitted when the ships are at berth or maneuvering in or out of berth. We compare the 2019 cruise season with Seattle’s 2018 emissions to avoid the unusual pandemic year of 2020. (Seattle publishes inventories only for even years.) In 2020, Seattle changed how it counts emissions, and applied these changes to all prior years, so we use the updated 2018 numbers from Seattle’s 2020 inventory.

(2) See PSEI, p.61, for a map of the area covered.

(3) See PSEI, p. 62, for information about data collection, and Appendix B for estimating methodology.

(4)ibid., p. 66, Table 3.3.

(5)Myclimate provides an overview of its methodology and sources; it uses the data set ecoinvent 3.6 and the IPPC 2013 evaluation method.

(6) A plausible scenario of room assignments suggests the underestimation may be as much as 11% of emissions.